It is a fact of life that interpreting is not all fluffy clouds and rainbows – we will be put in difficult situations in our line of work. Court interpreters may deal with relatively benign cases like running a stop sign; or they may be assigned a murder. Likewise, medical interpreters may be assigned routine check-ups, or may have to explain to a patient that they have terminal cancer. These situations can be incredibly hard to deal with, but they are part of the job.

All that being said, there are healthy and unhealthy ways to deal with this kind of traumatic material. Our physical and mental health is extremely important, and working with these difficult situations can create very real problems for us interpreters not just in our work, but in our personal lives as well. In this blog, we’ll be discussing self-care for interpreters and how you can deal with the effects of traumatic material when it comes up.

Vicarious Trauma, Burnout, Compassion Fatigue and their Effects

Vicarious trauma, burnout and compassion fatigue are three of the most common ailments interpreters experience in relation to traumatic material. They all come about through the “absorption” of another person’s trauma or hardships and they all have very real physical and mental consequences.

Vicarious trauma (VT) is best understood as taking on another person’s trauma through the process of empathy, and the transformation of the interpreter’s or other helper’s inner sense of identity and experience. Interpreters deal with this especially often, due to the fact that we are conduits for our clients – we become that person as we communicate what they are saying in the first person. Vicarious trauma can affect your perception of the world and your reality, and can create all kinds of mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and even addiction to substances, depending on how one copes.

Some common signs of VT include having difficulty talking about one’s feelings, worrying that one isn’t doing enough for their clients, diminished joy toward things one once enjoyed, withdrawal and isolation, and diminished feelings of satisfaction and personal accomplishment. One of the most common ways people with VT cope with their experiences is by trying to ignore the emotions they are feeling, and insisting that “everything is okay.” It is important to recognize, however, that it is okay to not be okay and to recognize that you are having difficulty.

Burnout is a similar condition that comes from a state of chronic stress – stress that is constant and cannot be “turned off.” Every one of us has our breaking point or limit to how much stress we can endure, and burnout arises when we surpass that limit. It’s important to note that burnout doesn’t happen suddenly; it is much more subtle, and slowly creeps up on us in practice, which makes it more difficult to notice.

The main signs of burnout are physical and emotional exhaustion, cynicism and detachment, and feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment. This can include ailments like insomnia, forgetfulness and impaired concentration, and even physical symptoms like chest pain, dizziness, or frequent headaches. This is not to say that if you get a headache every week or so that you are burnt out, but it is to say that you should be aware of all of these signs and assess the amount of stress in your life when you feel it necessary.

Compassion fatigue is also known as secondary traumatic stress, and is characterized by a gradual lessening of compassion over time. This comes about from dealing with victims of traumatic events, as we can become jaded to these experiences after being trying to be constantly empathetic and compassionate in these situations. Common signs of compassion fatigue are a feeling of hopelessness, a decrease in experiences of pleasure, constant stress and anxiety, sleeplessness or nightmares, and a pervasive negative attitude. All of this can lead to a decrease in productivity, inability to focus, and the development of new feelings of self-doubt and incompetency.

So, now that we know all of the bad things that can come about from dealing with these traumatic events, what can we do about them, how can we take care of ourselves and how can we prevent these things from happening to us?

Self-Care Strategies to Prevent These Ailments

There are a number of ways to deal with the overwhelming feeling of stress. The first is meditation. Taking even 10 minutes a day to meditate gives our minds time to decompress and revert to a sense of being, rather than the constant “doing” of our daily lives. There are several resources to help you get started, such as apps that you can download onto your cellphone that guide you and teach you how to meditate. It may seem silly, but it really does make a huge difference.

Another way to deal with these feelings is to assess the way you cope with them. Use of drugs or alcohol is always discouraged, as these can only serve to amplify the feelings of stress in the long-term. Likewise, constantly trying to reframe the situation can be helpful in some instances, but we must be careful not to lie to ourselves and insist that everything is fine when it is not.

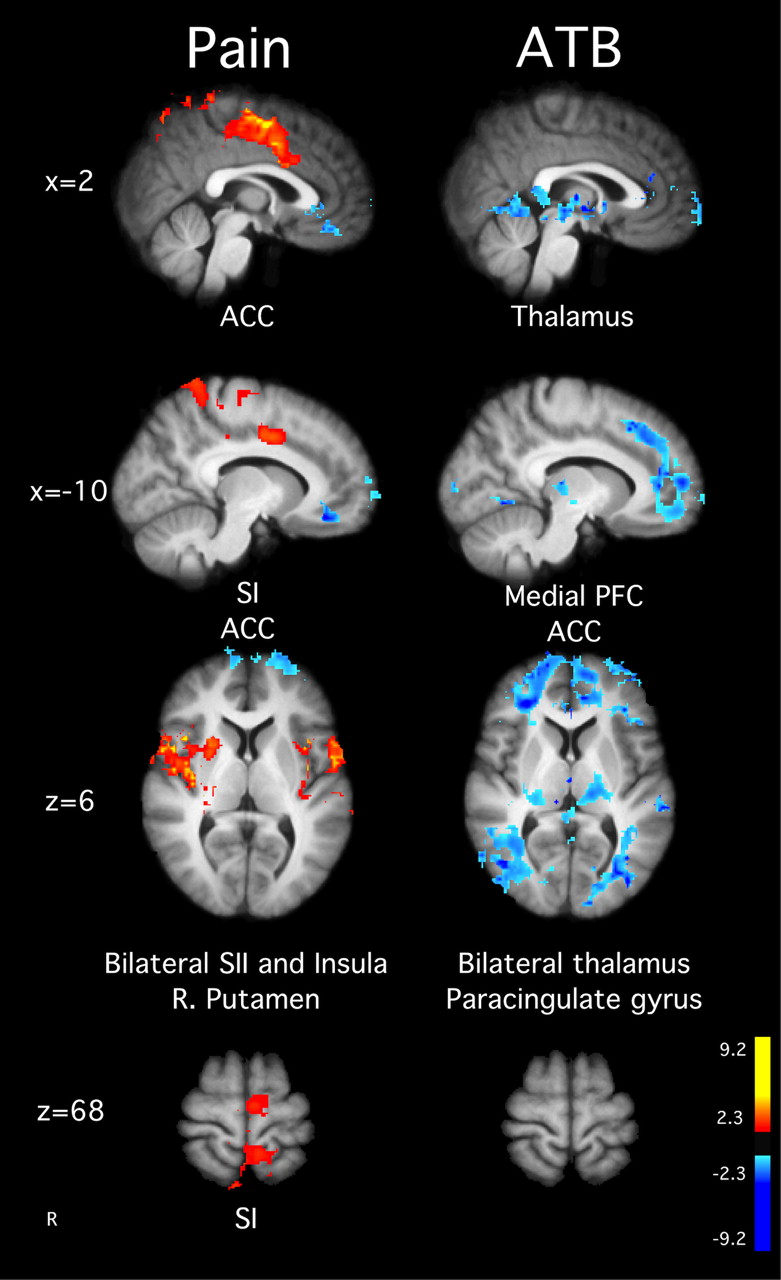

Finally, one of the most effective ways of reducing stress is to exercise, or to do something that you enjoy. These two things, especially if they are happening at the same time, are known to switch off pain receptors in the brain, both emotional and physical. Like meditation, it gives your brain a much-needed break from the stress you’re experiencing and gives you time to focus on something else. For more information on the effects of meditation on the pain responses of the brain, click on the image to the right which takes you to a study on this topic.

All of these strategies help to maintain your mental and emotional health. Try to find what works for you, and be aware of the warning signs of emotional trauma. If you have realized that you may be dealing with one or more of these ailments, know that it is okay to seek out help – you don’t have to deal with it by yourself. Interpreters are humans too – and while our jobs are important, it is just as important to care for ourselves.

Have you dealt with difficult or traumatic material in your field before? If so, how did you deal with it? What strategies worked for you, and which didn’t? Leave a comment below, and check back next week for another edition of Links Interpreters Love.

– William Cerkoney

4 Responses to LIL: Caring for Yourself; Dealing with Traumatic Material as an Interpreter